“Is it live or is it Memorex?”

That advertising slogan from the early 1980s hinted that the quality of a Memorex audio cassette would be so good that users couldn’t tell if they were listening to something live or something on tape.

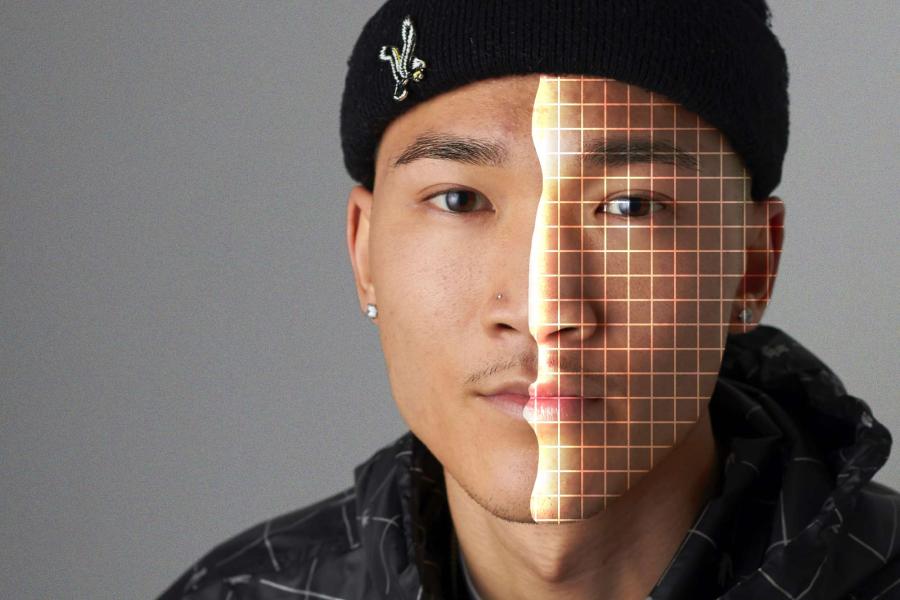

Fast forward 35 years and the same question could apply to writing generated by an AI program called ChatGPT. The game-changing app was released in November and is now so popular it’s sometimes impossible to get onto its website.

Faculty members this winter are coming to grips with artificial intelligence applications that can draft student papers seemingly flawlessly – or even with flaws, if requested. Instead of copying existing works, these AI applications can create a new work, using a text-based AI algorithm that has been trained on massive online databases.

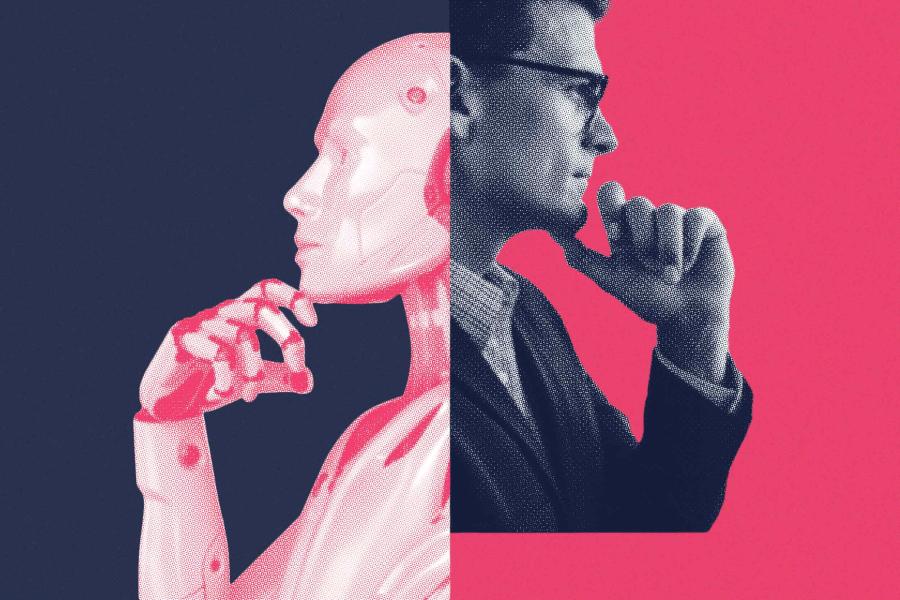

“The tools are leveraging what is known as generative AI,” said Michael Palmer, director of the University of Virginia’s Center for Teaching Excellence. “That means they’re not making guesses. It’s not a predefined set of responses. It’s not pulling a line of text out of the web. It’s generating responses from massive datasets. And it’s just based on probability and patterns, so it can write fluent, grammatically correct, mostly factual, text – instantly. All the user has to do is give it a few prompts, which the user can refine with a series of follow-up prompts.”

Palmer made a distinction between generative and predictive AI. Predictive AI guesses what the writer wants to say, based on word patterns and previous behavior. Google’s Gmail application, which anticipates what you want an email to say next, is an example, as are text programs that guess how you want to finish a sentence. But generative AI creates from scratch, using algorithms that have learned from data from the internet.